Attracting and retaining top talent to an in-house legal department

A version of this article first appeared in Corporate Law Department Management 2011 - A Practical Guide

Click here to view a PDF version of the article.

A political headache - the need to justify head-count

Lawyers are expensive; they epitomise high value human capital. If you are the Head of Legal in a commercial concern you will doubtless be fully aware that your department is usually the most, or amongst the most, expensive per-head cost of any in the organisation. This axiom, combined with the fact that legal is nearly always perceived as a cost centre in most companies, makes justifying existing legal headcount, let alone trying to increase it, politically problematic for Heads of Legal. Unfortunately, as the need for quality in-house lawyers continues to increase so too will the challenge of justifying legal headcount and ensuring your lawyers are paid “market rate” compensation relative to their law firm peers.

The growth of in-house commerce & industry legal departments

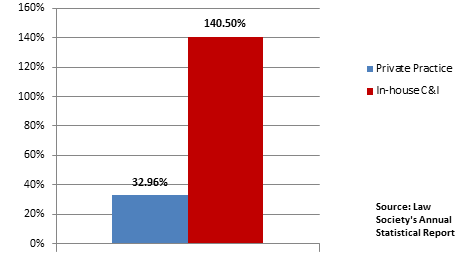

Over the past decade the number of qualified lawyers within commercial organisations and financial institutions in England and Wales, (defined by The Law Society as Commerce & Industry (C&I)), has grown at an astonishing rate. In the UK, between 2000 and 2010 the number of solicitors with practicing certificates in C&I grew by more than 140% so that by 2010 nearly 11% of all qualified solicitors were working in-house in C&I {1}. Moreover, whereas 15 years ago the majority of in-house lawyers in the UK were sole counsel, today that applies to less than a quarter of legal departments.

% increase in solicitors in-house in Commerce & Industry versus Private Practice

(2000-2010)

Regardless of what happens in the wider economy the number and proportion of lawyers in C&I, relative to those in commercial law firms, will continue to increase for the foreseeable future for three main reasons:

1. increased regulation, in particular large set-piece governance legislation - such as the UK Bribery Act (2010) or the US Sarbanes-Oxley Act - has demanded that companies review their legal risk;

2. increased enforcement of pre-existing regulations, as UK and European regulators are now imposing severe sanctions on companies and, crucially, individual directors and officers; and

3. cost - generally, but not always, in-house lawyers save costs by reducing external legal spend on law firms.

The Importance of quality over cost

The traditional role of the in-house lawyer is primarily to save costs. If the cost of necessary external legal spend (on law firms) exceeds the projected compensation of an in-house lawyer, most FD’s would agree there is a prima facie case for hiring or maintaining the latter. Of course commercial lawyers will often save costs in a much more fundamental way; depending on the organisation, a well drafted contract can save hundreds of millions of pounds (although this may never be tested in court if the contract is truly watertight). Happily over the past twenty years there has been a move away from the simple cost saving criteria above and it is increasingly recognised by more sophisticated organisations that the real purpose of an in-house lawyer is to:

1. speed up management decision making processes;

2. increase management options and, most importantly; and

3. reduce legal risk.

In large part, this shift has come about because the sanctions, both civil and criminal, imposed on individual directors and officers of companies has forced management to focus on the hiring and retention of quality in-house legal and compliance personnel and what their real function should be. Indeed it is ironic that a good in-house lawyer will often significantly increase external legal spend, at least in the short term, because, by fully understanding the business, they discover ticking time bombs (in the form of illegal practices) which require outside legal assistance to remedy.

In spite of the above, most commercial organisations still expect their legal departments to justify themselves on a costs basis and this remains a significant challenge for Heads of Legal.

Where to find talent

In the UK, nearly 90% of qualified solicitors working in C&I have previously worked in a law firm and currently fewer than 3% of trainee solicitors are in C&I. Because most C&I teams remain very small (in the UK 70% have five or fewer legal personnel {2}) by far the most common place to source talented lawyers is from law firms. This will remain so for the foreseeable future. This inexorable link has profound implications for both hiring and retaining specialist lawyers and, for that reason, it is important to keep abreast of developments in law firm compensation because, however obliquely, this sets C&I compensation in both the UK and the USA.

Benchmarking compensation

Because in-house legal departments are generally small (see above) and legal hires relatively infrequent, one of the greatest difficulties is accurately benchmarking salaries for your existing and new legal personnel.

You and your HR department should not overly rely on industry salary surveys such as those produced by the larger recruiters or benchmarking companies. Unlike with law firms, the range of factors affecting in-house legal compensation is so varied as to make drawing a line of “best fit” on a graph almost impossible. The result is that surveys of in-house salaries tend to be less accurate than those for law firms. Moreover, law firms will generally make salary information public or will have reliable, detailed data to respond to surveys; the same is generally not the case for in-house legal departments unless they are highly localised and “of a type”, such as investment banking, whose legal departments tend to be large and comprised of capital markets lawyers based in major trading centres such as central London or Manhattan.

For accurate benchmarking you will need to take into account: industry sector, the size of the organisation (this only really impacts senior level compensation), the physical location of the role, seniority (or scope of the role) and, increasingly, the specialisation of the lawyer you require.

Of these factors most will be self-evident, however, specialisation is one which usually takes some explaining to those HR teams in-experienced in legal hires. Twenty years ago C&I lawyers were nearly always hired to undertake and oversee commercial contracts. Whilst this is still largely true, it has become more common than not for C&I departments to hire specialist lawyers. The reason for this change is the same as that driving the improvement in quality of all in-house legal teams - increased and sustained governance legislation and enforcement by regulators. Moreover, legal risk is elevated with the increasing complexity of the products and services being offered by corporations.

The relative cost of specialist lawyers is determined by two main factors:

1. supply and demand; and

2. the compensation paid to the specialist in private practice law firms.

Exceptions aside, the main problem with hiring legal specialists is that they tend to be found in law firms which typically pay at least 10% more than in-house for virtually all industry sectors, except investment banking and certain niche financial services.

Amongst more experienced company officers and Heads of Legal the need for “A-grade” specialists is increasingly acknowledged - so much so that it is now not unheard of to find a specialist within a legal department earning more than the General Counsel or Head of Legal!

Benchmarking and law firms

From a retention and benchmarking perspective, it is as well to remember that the concept of assistant level lockstep in law firms (where compensation automatically rises with every additional year of post-qualified experience) is still largely intact, so that, most years, compensation at UK and US law firms increases faster than at even very high performing corporations. Generally even where lawyers moving in-house are initially paid the same as they are in private practice, after two or three years their compensation inevitably starts to trail that of their law firm contemporaries – a situation which if unchecked can lead to morale issues and elevated attrition rates in your department. In relation to in-coming hires a very real danger, in failing to secure sufficient budget, is that you will get a second rate lawyer who, although initially less expensive, will eventually need their work corrected by others within the department or an outside law firm. Worse still, they may fail to undertake their primary role - reduction of legal risk - for which you will ultimately be held responsible.

How to benchmark

Because benchmarking of compensation is very important and should not be confined to “incoming hires” you should take this as a regular part of your role and avoid outsourcing it to HR. After reading any generic salary surveys in relation to law firm or in-house compensation, you should take time to speak to industry rivals, peers and switched on recruiters. After you have done this, present your edited findings to the business - ideally you should try and get another company officer, such as the FD, onside before presenting your findings to HR. If recruiting, always benchmark before the budget is set because the alternative will often be a time consuming recruitment process followed by the withdrawal of the headcount, or the politically clumsy need to apply for additional budget.

Retention

Usually the undoubted lifestyle benefits of C&I outweighs, at least for lawyers already pre-disposed to move in-house, a 10-15% compensation differential with law firms. However, once in, the (generally small) size and necessarily flat structure of most C&I teams makes meaningful promotion for lawyers impossible. This is probably the single greatest source of lawyer dissatisfaction and takes considerable management imagination and input to overcome.

Getting buy-in from the business

The challenges in protecting yourself from both voluntary and involuntary departures of good people are vast and there is of course no simple answer. Nevertheless, one factor which can really mitigate against both is to prove your department’s value to the business. Essentially this involves you sitting down with the main company officers and business heads, and agreeing with them what it is they want from their legal department. Once you have this you can formalise these objectives against measurable departmental benchmarks or key performance indicators (KPIs). You can then set agreed objectives for each of your legal personnel based on these KPIs and measure them against these criteria.

If properly implemented, the result of the above is hugely energising both for your lawyers and, I would suggest, yourself. Moreover, it elevates the prestige of the department - automatically highlighting its all-important “value” to the business. Once established, you will find this assists in retention, recruitment, general morale and operational efficacy. A more detailed explanation of this process is beyond the scope of this article.

There are many claims made for the benefits of this form of proactive management; some notable legal departments within sizable global companies have extrapolated this further - with the result that they purport to be net sustainable revenue generators for their organisations {3}.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, the uniquely expensive per head cost of non-revenue generating legal departments makes your role of attracting and retaining top talent particularly challenging and labour intensive. It requires that you spend a great deal of down time educating the business and your own team as to the real value of the legal department. It requires that you:

1. regularly benchmark your team against both market peers and law firms;

2. constantly “prove” your value to the business by demonstrating to management that the legal department: speeds up management decision making processes, increases management options, reduces legal and reputational risk and, where possible, saves cost; and

3. agree with management what it is they want from their legal team, agree KPIs and set measurable objectives for your team and actually objectively measure them against these.

None of this is easy and it will, at times, appear a completely thankless task. However, lawyers rarely leave their position for money alone - by far the most common reason is because they feel “undervalued”. Indisputably, legal departments which are headed by individuals who have taken the actions above, find that they have lower attrition rates and exert a much stronger pull for in-coming lawyers who sense that the department is regarded as a “value add” rather than a “cost”.

© Edwards Gibson 2012

Footnotes

1. The Law Society: Trends in the solicitor’s profession Annual statistical reports, 2000-2010.

2. The Law Society, 2008 Corporate counsel – a profile

3. Martindale-Hubbell/ LexisNexis 2010: “The Profitable Legal Department”

-

What’s behind the escalating three-year bull run in Big Law Partner Hires in London and is it sustainable?

-

Year End Big Law Tie Ups - and the standout is Hogan Lovells Cadwalader

-

“To: Cc or not Cc” – Clifford Chance's subversive new branding

-

Two Big Law Summer Weddings … and an Anniversary

-

Freshfields’ Non-Share Home Turf Handicap

-

Big Law Jenga: How Private Capital Stars Are Making Elite Firms Unstable

-

Big Law’s Brave “Few”, Their Inevitable Pyrrhic Victory, and Why This Is Still a Tragedy for The Rule of Law

-

No Accounting for the Big Four in Big Law

-

MIPIM 2025 Doppelgänger Style!

-

"Memery Loss" London Law Firm Memery Crystal Sinks

-

Lawyers should remember that the financial success of Big Law is predicated entirely on the Rule of Law

-

Paul Weiss - The invasive species that upset the London Big Law ecosystem

-

Paul Weiss - Happy Birthday to BigLaw's Apex Predator

-

Paul Weiss - Blackjack!

-

Breaking The Circle - the real significance of Freshfields pay bonanza is far more profound than just another Big Law salary arms race.

-

A lawyer's progress to partnership... and the closing window of opportunity

-

Linklaters – Welcome to the “Hotel California” of Big Law; “You can check out anytime you like but you can never leave”

-

The Pecking Order at MIPIM; believe it or not Real Estate Lawyers are not at the bottom!

-

Parallels in Peril, two midsize law firms – Axiom Ince and Stroock & Stroock & Lavan – collapse in the same month

-

And you thought $20 million was a lot for a lawyer…

-

Legal Upheaval: Kirkland & Ellis and Paul Weiss Exchange Blows

-

So, it’s A&O Shearman!

-

Real Estate lawyers - beware the £1,000 fish, and the true meaning of MIPIM … (literally)

-

Previous Issues of Partner Moves

-

Edwards Gibson Methodology for Compiling Partner Moves

-

Quantifying your following and writing an effective law firm business plan

-

Sample law firm business plan

-

The Partnership Track and Moving for Immediate Partnership

-

Legal directory rankings and their effect on lawyer recruitment

-

Restrictive Covenants and Moving on as a Partner

-

Competency Based Interviews - an overview

-

Verbal reasoning tests

-

Recruiting in-house lawyers - a guide for General Counsel/Legal Directors

-

London Law Firm Assistants Salary and Bonus, Trends and Predictions 2014-15

-

Compensation Packages for Expat US Lawyers in London – ‘COLAs’ Explained

-

London Law Firm Assistants Salary and Bonus, Trends and Predictions 2013-14

-

The In-House Triumph over Law Firms - A Pyrrhic victory?

-

London Law Firm Assistants Salary and Bonus, Trends and Predictions 2012-13

-

London Law Firm Partner Compensation 2012-13

-

The rise and fall of the elite investment bank lawyer

-

Attracting and retaining top talent to an in-house legal department

-

London Law Firm Assistants Salary and Bonus, Trends and Predictions 2011-12

-

FAQs about legal recruiting

-

The successful business lawyer