A lawyer's progress to partnership... and the closing window of opportunity

Download the PDF of this article here >>

1st May 2024

Written by Scott Gibson

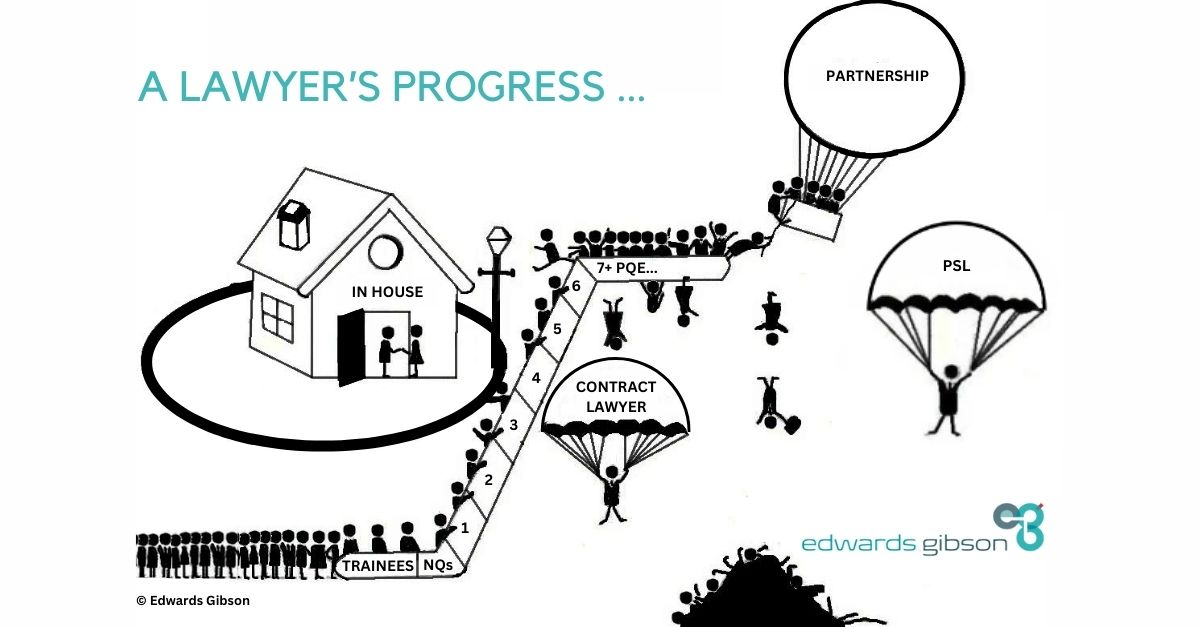

Way back in 2013, I drew this (admittedly simplistic) pictorial representation of the typical career progression of a lawyer in a BigLaw firm. At the time, noted legal commentators were predicting, as they seemingly always are, that the traditional law firm model was doomed. The thing is, more than a decade on, not much has changed. The profession remains crowded at the bottom (as a celebrity lawyer once told me, “law pays well for average ability”), so the top law firms are never short of pre-qualification applicants. It thins out in the middle, thanks to a combination of: burn-out (after all, law can be brutal!), career epiphanies, the supposed “lifestyle” benefits of moving in-house, and a perennial law-firm on law-firm talent war for associates at the 2-6 post-qualification experience [PQE] level (for law firms, these are the most accretive and hence most poached individuals).

After that, it starts to get crowded again … whilst partnership is admittedly no longer the be-all-and-end-all that it once was, for most survivors it’s still worth the fight. The problem is that partnership promotions are overwhelmingly limited by “business case” and, unfortunately, no law schools (and very few law firms) make clear that client winning skills nearly always trump raw legal talent in both the race to partnership and progression thereafter. If you can be a brilliant lawyer and a brilliant salesperson, giddy-up! BUT, if you do have to choose, the truth is it’s better to be an “adequate” lawyer and a “good” salesperson than be a “good” lawyer and an “adequate” salesperson.

Partnership progression is a bottleneck, so beyond 9 years PQE, left alone, the increasingly concertinaed non-partners become a problem for law firms. Non-partners are rarely attributed with client origination credits and, without these to defray their cost, these senior lawyers become disproportionately expensive, particularly as it is difficult for firms to charge them out at levels sufficiently higher than those of their mid-level colleagues. Moreover, because the senior lawyers are, by definition, more experienced, they tend to push to undertake the more complex senior level work. This can starve promising mid-levels of the experience they themselves need to make partner and, just as important from the law firm’s perspective, damage the morale of these harder to replace lawyers. This conundrum, rarely explicitly owned up to by law firms, is a challenge which can only ever be partially offset by internal alternative career paths – there are only so many plateau Counsel, Legal Director or Professional Support Lawyer roles a given department can sustain and so, at this level, law firms tend to welcome natural attrition. Indeed, where senior non-partner turnover is sluggish, law firms will often quietly help it along – I actually know someone whose spouse’s primary job function at their US headquartered global law firm, is to (surreptitiously) “shoot” blocked senior associates!

Regardless, however unfair it may seem, in most instances, there is a relatively narrow window (currently between 9 and 14 PQE) when partner promotions occur. Beyond this there appears to be an unwritten rule that, however good a lawyer is, or whatever the extenuating circumstances of their previous failure to be promoted, their time has passed. Whilst there are of course many exceptions to the above, for associates it pays to be mindful that the partnership clock is always ticking.

Lest the above seem overly bleak, aspiring lawyers should take comfort in the fact that overcrowding in law is nothing new – back in the 18th century, when advised not to become a lawyer because the profession was full, Daniel Webster, the “expounder of the (US) constitution”, is said to have replied: “there is always room at the top”!

©Edwards Gibson

Download the PDF of this article here >>

-

What’s behind the escalating three-year bull run in Big Law Partner Hires in London and is it sustainable?

-

Year End Big Law Tie Ups - and the standout is Hogan Lovells Cadwalader

-

“To: Cc or not Cc” – Clifford Chance's subversive new branding

-

Two Big Law Summer Weddings … and an Anniversary

-

Freshfields’ Non-Share Home Turf Handicap

-

Big Law Jenga: How Private Capital Stars Are Making Elite Firms Unstable

-

Big Law’s Brave “Few”, Their Inevitable Pyrrhic Victory, and Why This Is Still a Tragedy for The Rule of Law

-

No Accounting for the Big Four in Big Law

-

MIPIM 2025 Doppelgänger Style!

-

"Memery Loss" London Law Firm Memery Crystal Sinks

-

Lawyers should remember that the financial success of Big Law is predicated entirely on the Rule of Law

-

Paul Weiss - The invasive species that upset the London Big Law ecosystem

-

Paul Weiss - Happy Birthday to BigLaw's Apex Predator

-

Paul Weiss - Blackjack!

-

Breaking The Circle - the real significance of Freshfields pay bonanza is far more profound than just another Big Law salary arms race.

-

A lawyer's progress to partnership... and the closing window of opportunity

-

Linklaters – Welcome to the “Hotel California” of Big Law; “You can check out anytime you like but you can never leave”

-

The Pecking Order at MIPIM; believe it or not Real Estate Lawyers are not at the bottom!

-

Parallels in Peril, two midsize law firms – Axiom Ince and Stroock & Stroock & Lavan – collapse in the same month

-

And you thought $20 million was a lot for a lawyer…

-

Legal Upheaval: Kirkland & Ellis and Paul Weiss Exchange Blows

-

So, it’s A&O Shearman!

-

Real Estate lawyers - beware the £1,000 fish, and the true meaning of MIPIM … (literally)

-

Previous Issues of Partner Moves

-

Edwards Gibson Methodology for Compiling Partner Moves

-

Quantifying your following and writing an effective law firm business plan

-

Sample law firm business plan

-

The Partnership Track and Moving for Immediate Partnership

-

Legal directory rankings and their effect on lawyer recruitment

-

Restrictive Covenants and Moving on as a Partner

-

Competency Based Interviews - an overview

-

Verbal reasoning tests

-

Recruiting in-house lawyers - a guide for General Counsel/Legal Directors

-

London Law Firm Assistants Salary and Bonus, Trends and Predictions 2014-15

-

Compensation Packages for Expat US Lawyers in London – ‘COLAs’ Explained

-

London Law Firm Assistants Salary and Bonus, Trends and Predictions 2013-14

-

The In-House Triumph over Law Firms - A Pyrrhic victory?

-

London Law Firm Assistants Salary and Bonus, Trends and Predictions 2012-13

-

London Law Firm Partner Compensation 2012-13

-

The rise and fall of the elite investment bank lawyer

-

Attracting and retaining top talent to an in-house legal department

-

London Law Firm Assistants Salary and Bonus, Trends and Predictions 2011-12

-

FAQs about legal recruiting

-

The successful business lawyer